Today I will make my first presentation as a licensed librarian for a group of 100 public school administrators, mostly principals, at the annual Teacher-Librarian Seminar-Workshop sponsored by the Children's Library.

I was invited to be a speaker at the event because of what I have written in this blog, specifically "Librarians as Leaders." This relatively fresh graduate (2004) has the (mis)fortune of being the speaker after the director of the National Library. Wish me luck.

The rest of this post contains the slides and full text of my presentation.

Let me begin by giving you an overview of my presentation.

The original title was supposed to be “So what if we don’t have cash?” But this tends to give the impression that money is not important. However, since money is, in fact, important, I decided to change the title.

“Principal factor” is not a term that is as common as “teacher factor,” which refers to the impact of a teacher’s performance—or lack thereof—on student achievement. The principal factor, as I use it in this presentation, refers not just to the principal’s role in the development of the library, but also to the most important factor that affects library development.

We’ll be going through some basic facts about the state of public school libraries just to make sure that my assumptions are correct. After all, you are the best persons to ask about the state of your libraries.

We’ll also look at some of the factors that affect the development of school libraries. Why is it that some libraries develop more than others? Could it be that they just have more money?

And finally, what can we do about the situation? I hope all of us are here today because we want to improve our libraries.

Why am I here? I have already been introduced, but I think I need to tell you more about myself because, if I were in your shoes, I’d also be wondering, “Sino ba siya?”

The main reason I’m here is that I was invited on the basis of an essay I wrote, which was based on my thesis, entitled “Factors influencing the development of public school libraries.” I am also a licensed librarian who knows what it means to work with pupils, teachers, principals, and administrators—because I was once a teacher myself.

I was also a government employee for a short while, but it was long enough for me to learn just how difficult it can be to try to implement changes with so many constraints. In addition, both my retired parents were once government employees. My mother, in particular, was a public school teacher at T. Alonzo Elementary School in Project 4, Quezon City.

In fact, when I told my parents that I would be speaking to a group of principals, they told me to highlight the fact that they and their brothers and sisters—all seventeen of them—were products of the public school system.

I may not have the benefit of your experience, but I’d like to think that I understand your situation. And so, I do not intend to tell you what to do or prescribe solutions that will be difficult to implement. I hope you will find my suggestions realistic and reasonable.

Why you are here? When I was gathering data for my thesis, I spoke with school principals before talking to librarians because I needed to get their approval and because I wanted to get a bigger picture of the school’s situation.

When I told one of the principals the title of my thesis, she said, “There’s no need to study the matter; you just need money.” Do you agree? Well, as it turned out, money is important, but it is not the only factor.

The principal factor is much more important. Later, I will tell you about two libraries that had money but one was more successful than the other. What was the difference? The principal factor. I hope you are here today because you believe that it takes more than “just money” to set up a library.

In addition, I’d like to think that you’re here because you are interested in upgrading the reading skills of your pupils and that you wish to improve your school library. Why? Because you recognize that the library has an important role to play in the development of your pupils.

Please consider the following findings and think about whether they are applicable to your library:

Books are merely accessioned, but neither classified nor catalogued.How many of these would you agree with? Well, these findings also appear in your handouts, but what you will not find there is that I am quoting from a thesis written by Concordia Sanchez in 1940.

This is accompanied by an unbalanced or disproportionate distribution of books.

The housing conditions provided for the library, if any, are poor, and the furniture and equipment are inadequate.

The library is not open long enough for students to use it to the fullest extent. Opening the library is only a matter of “if time permits” for the librarian. Some schools do not even open their libraries at all.

Librarians have not had any training in library work.

How much has changed since then? Please approach me after my presentation if you think that there have been a lot of changes.

I believe that not much has changed since 1940 because of certain constraints. What are some of these difficulties?

In a book published in 1999 about the prevalence of corruption in the Philippine public school system, the canteen is given a section all its own, whereas the library is never mentioned. Why? Because there is money to be made through the canteen, but none through the library. Please tell me if I’m wrong, but no budget allocations are made for most school libraries and, unlike private schools, you are not allowed to collect library fees.

A high-ranking administrator once told me that it is difficult to justify hiring a full-time librarian if you do not even have enough teachers. And so, overworked and underpaid teachers—who have little or no training in library work—are also assigned to be librarians.

Then again, some teachers become temporary “librarians” because—forgive me, but I don't know how else to say it—they are either going to retire soon or cannot teach effectively. There’s also property accountability, which dictates that lost books will be charged to the account of the person responsible for the books.

No money, no time, no training. And the threat of paying for lost books. Can we, therefore, blame librarians for the state of libraries today? Not really.

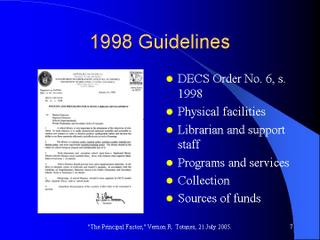

Have you heard of the “Guidelines on the Implementation of School Library Policies and Programs” issued in 1998 by the then Department of Education, Culture and Sports (DECS)? It should properly be called Enclosure No. 1 of the DECS Order No. 6, s. 1998, signed by Ricardo Gloria—but let’s refer to it as the 1998 Guidelines. Copies are available in your handouts. [For an online copy of the DECS Order, see "The State of Public School Libraries."]

The 1998 Guidelines set forth what should be available in public school libraries in terms of:

- Physical facilities – If, for example, you have an enrollment of 500, then your library should have a floor area of at least 72 square meters.

- Librarian and support staff – If you have 2,000 pupils, then you should have one full-time librarian and one part-time teacher-librarian.

- Programs and services – This includes library orientation during the opening of classes and library lessons as part of the curriculum.

- Collection – Encyclopedias, dictionaries, plus magazines, newspapers and professional books for teachers and librarians.

- Sources of funds – To pay for all these, the 1998 Guidelines state: “Library funds shall be 5-10% of the school funds (based proportionately) as released by the Division office.”

In spite of constraints, some public school libraries have developed and flourished to a point that they actually exceed the requirements of the 1998 Guidelines. You have probably heard of some of these success stories because of articles that have appeared in magazines and newspapers.

Star Teacher has featured libraries sponsored by Hongkong and Shanghai Bank. Articles have also been written about school libraries chosen by Books for the Barrios to be part of its Models of Excellence program. There are others, too, but almost always the focus was on results.

We hardly ever read about the difficulties that had to be overcome. What happened between the “before” and the “after”? How exactly can others replicate their success? Readers may, in fact, get the impression that all you need to have a good library is a donor who has money. But is it really just about money?

The following factors are taken from the findings of a project in the United States called Library Power. I will not go into each one of the factors, but if you look at them carefully, you will see that resources—or money—is just one of many. Which factor is the most important? Which one is the principal factor that will lead to success?

You may also look at these factors as a guide. Ask yourself: How many of these factors are present in your school library? Do you have a vision? Have you created an environment in which change can occur? And so on…

In my thesis, I looked at the development of seven public secondary school libraries in Quezon City. Using the 1998 Guidelines, I quantified the level of development of each library, and focused on the two school libraries with the highest scores. By comparing these two libraries, I was able to determine that both were “developed” according to the 1998 Guidelines, but one was more developed than the other. Not because one had more money, but because one had a factor that the other did not—the principal factor: leadership.

Eleven school libraries in Quezon City were automated as part of the SB e-Library project through the leadership of Mayor Sonny Belmonte, Division Superintendent Victoria Fuentes, Asst. Division Superintendent Meleda Polita, and the school principals and librarians.

The two libraries with the highest scores in my study were part of the SB e-Library project. And that’s why they were the only ones among the seven included in my study that had most of the factors needed for development.

This is a photo of the Juan Sumulong High School e-Library, the library with the highest development score. The other library—please do not ask me to identify it by name—scored much higher than the other five, but it was not a close second.

Sumulong had the principal factor, but the other did not. Please don’t get confused. The principal of Sumulong High School, Noemi Moncada, played a major role in raising funds for the library, but the other principal also raised funds for her school’s library. So leadership was present from the mayor to the principal in both schools. What was the difference? The Sumulong librarian was—and is—a leader.

Susan Torres, Sumulong’s librarian, has the necessary leadership skills that the librarian from the other school does not. One of the most important things that a good leader does is to get people to listen, to pay attention. And Susan Torres, with her principal’s support, gets people to listen.

What do school libraries need? The principal factor.

Leadership is very important. Not just at the librarian’s level or the mayor’s level, but at all levels. And it is especially important at the principal’s level. You, the principal, are a factor. Please correct me if I’m wrong, but directives from the Secretary of Education will have no effect if principals do not believe in them. In fact, if the principal champions the cause of the library, all other factors will follow. And if the principal does not believe libraries are necessary? Even if the librarian is very good, not much will happen.

We need principals who will begin with the end in mind. We need principals who believe in the importance of the library. We need principals who will provide a convenient location for the library. And, more importantly, we need principals who will appoint the right person to take charge of the library.

The right person is someone who actually likes pupils and books. The right person will allow pupils to use the books. With the principal’s support, this person will have time for the library. This person will also have to be a leader because you, the principal, won’t be able to do everything. This person will have to be good at public relations—not just with pupils, but also teachers, parents and possible donors.

Finally, the one factor that was not yet present in any of the libraries I visited: accountability. This factor does not refer just to property accountability. I am referring to how useful the library is. I am referring to test results. It’s very possible, after all, that an expensive, good-looking library will have no effect on learning.

If you would like to read further, I recommend that you look for Information Power: Building Partnerships for Learning (Chicago: American Library Association, 1998). It will probably not be available at any local bookstore, so you are better off checking with the nearest school of library and information science or the Internet.

You may also want to look at School Librarian in Action. Zarah Gagatiga, who will be speaking with the librarians this afternoon, owns this website where she talks about her experiences at Xavier’s Grade School library. She writes, of course, not from a public school perspective, but there is much that can be learned from her experience.

There is also Filipino Librarian. This is my own website. Here you will find the slides and full text of my presentation today, other things I have written about libraries in the Philippines, whether public or private, and resources freely available on the Internet.

Before I end, I would just like to repeat a few points.

Money is important. But there is something more important than money.

School libraries need leaders. And one of the most important leaders is the principal. After all, it is the principal who will choose the librarian, among other things.

Leadership is very important. All other factors will follow, including money, if you have a leader.

Maraming salamat po.